By Thornical Press –

November 8, 2025

Roman brick—the long, low-profile brick type inspired by ancient Roman prototypes—has carved an unlikely but enduring niche in American architecture. Its appeal is less about novelty than about a particular visual logic: elongated courses that emphasize horizontality, fine shadow lines at narrow mortar joints, and a hand-tooled, crafted presence that reads simultaneously classical and contemporary. The story of Roman brick in the United States is one of reinterpretation: an ancient typology adapted to new materials, new bonds, and new aesthetic aims.

The prototype for modern Roman brick lies in Roman imperial brickmaking: fired, kiln-made units that were often longer and flatter than the later medieval or modern bricks that followed. Those ancient bricks helped create long horizontal courses and were used in banding, vaulting, and polychrome effects across the empire. After a long European gap following Rome’s fall, the “Roman” profile returned as a deliberate historicist choice in nineteenth-century Classicism and the American Renaissance, when architects sought solidity and refined texture for public and cultural buildings. In the United States this revival first surfaced in institutional and civic architecture, then migrated to domestic work where the brick’s scale and rhythm could be exploited more intimately.

What sets Roman brick apart is both proportion and the way it is detailed. Typical modern Roman bricks are significantly longer and lower than standard modular units; their stretched profile lengthens perceived sightlines and creates bands that tie a building horizontally. When paired with thin recessed or struck mortar joints, each course becomes a fine shadow line—subtle but powerful in defining mass and plane. These qualities make Roman brick an ideal mediator between monument and human scale: from a distance it reads as solid and enduring, yet in close view it reveals craft, texture, and the small irregularities that anchor a building in the handwork of its makers.

Beyond proportion, Roman brick is a tool of articulation. Architects use it to emphasize datum lines—sills, lintels, cornices—or to create continuous bands that wrap corners without heavy interruption. In interiors, the long bricks lend hearths, feature walls, and lobby surrounds an understated elegance that standard bricks rarely achieve, because the elongated stretcher draws the eye along a plane rather than a vertical stack. In both public and domestic settings Roman brick can temper scale: a tall building gains horizontality; a long facade acquires a human rhythm.

Brick has always been both structure and surface; Roman brick pushes that duality further. Designers exploit its geometry in bonds and coursing that become decorative in themselves: running bonds that accentuate expanses, soldier courses that frame openings, and recessed joints that animate elevations with thin chiaroscuro. Contemporary masons and architects also experiment with rotated or raked courses, selectively angled bricks, and subtle color gradations to create murals or textured veils that read as both tectonic and painterly. The material’s restraint lends itself to disciplined ornament, where pattern emerges from repetition and proportion rather than applied ornament.

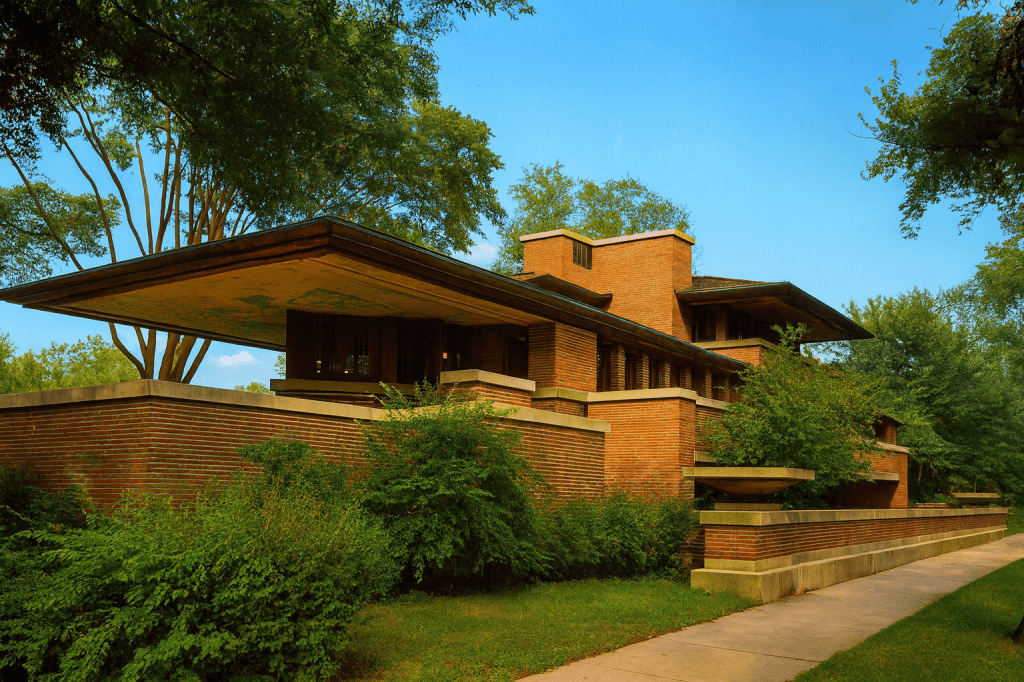

The twentieth century was pivotal: Roman brick moved from historicist reference into the vocabulary of modernism. Frank Lloyd Wright and his Usonian successors favored long, thin bricks to flatten elevations and bind interior to exterior, using stretcher courses to emphasize sheltering rooflines and terraces. That lineage continued into mid-century housing and institutional projects where the brick’s horizontality corresponded to the era’s ideals of openness and integration with landscape. Craftspeople and brick manufacturers responded with new molds and firing techniques, producing units that retained the Roman profile while meeting modern tolerances for strength and uniformity.

In the twenty-first century Roman brick has enjoyed renewed popularity among architects seeking durable, low-maintenance materials with a strong visual identity. Contemporary practices deploy Roman bricks not as mere pastiche but as a means to reconcile new construction with historic contexts, to craft facades that read with human scale, and to exploit brick’s environmental and longevity credentials. Recent work shows inventive uses: textured, curving facades that celebrate coursing; semi-permeable brick screens that act as sunscreens and privacy filters; and precise interior applications that celebrate mortar joints and shadow lines as part of a refined material palette.

Architects today approach Roman brick with a range of design agendas. One is contextual integration: in neighborhoods of older brick buildings, elongated units help new work read as a continuation rather than a counterpoint, because the stretched courses can be tuned to echo datum lines and cornices on adjacent structures. A second agenda is tectonic exploration: firms are bending the rules of brickwork—curving walls, corbelled projections, alternating header-and-stretcher patterns—to create subtle movement and lively shadow on otherwise planar facades. A third is material honesty paired with sustainability: several manufacturers now produce Roman-profile units with recycled content or optimized firing processes that reduce embodied energy, enabling designers to pair a classical aesthetic with contemporary environmental targets.

Roman brick’s artistic power lies in its ability to simplify visual complexity. Where ornate trim or heavy molding might call attention to themselves, elongated brickwork establishes a disciplined field in which light, joint width, mortar color, and coursing become the primary means of articulation. In the hands of a careful designer a facade of Roman brick can register as both austere and richly textured: austere in composition, textured in detail. That duality explains its appeal to architects who prize understatement over spectacle yet still require a tactile, crafted surface.

There are practical considerations that have shaped Roman brick’s modern use. Long, thin units demand precise laying and careful jointing; they reveal irregularities more readily than standard bricks. They also require attention to structural attachment and flashing in contemporary wall assemblies. When done well, though, maintenance needs are low and the material ages gracefully, acquiring patina without losing compositional clarity.

Roman brick endures in American architecture because it answers a set of perennial design problems: how to make buildings feel grounded and human-scaled, how to knit new work into older urban fabrics, and how to obtain a refined, tactile surface without resorting to applied ornament. Its proportions support design goals that matter now—sustainability, contextual sensitivity, and finely calibrated ornament—while its long history offers a visual shorthand of permanence. For architects and designers who value restraint, texture, and horizontal compositional strength, Roman brick remains one of the most eloquent and adaptable materials in the contemporary palette.