By Thornical Press –

December 22, 2025

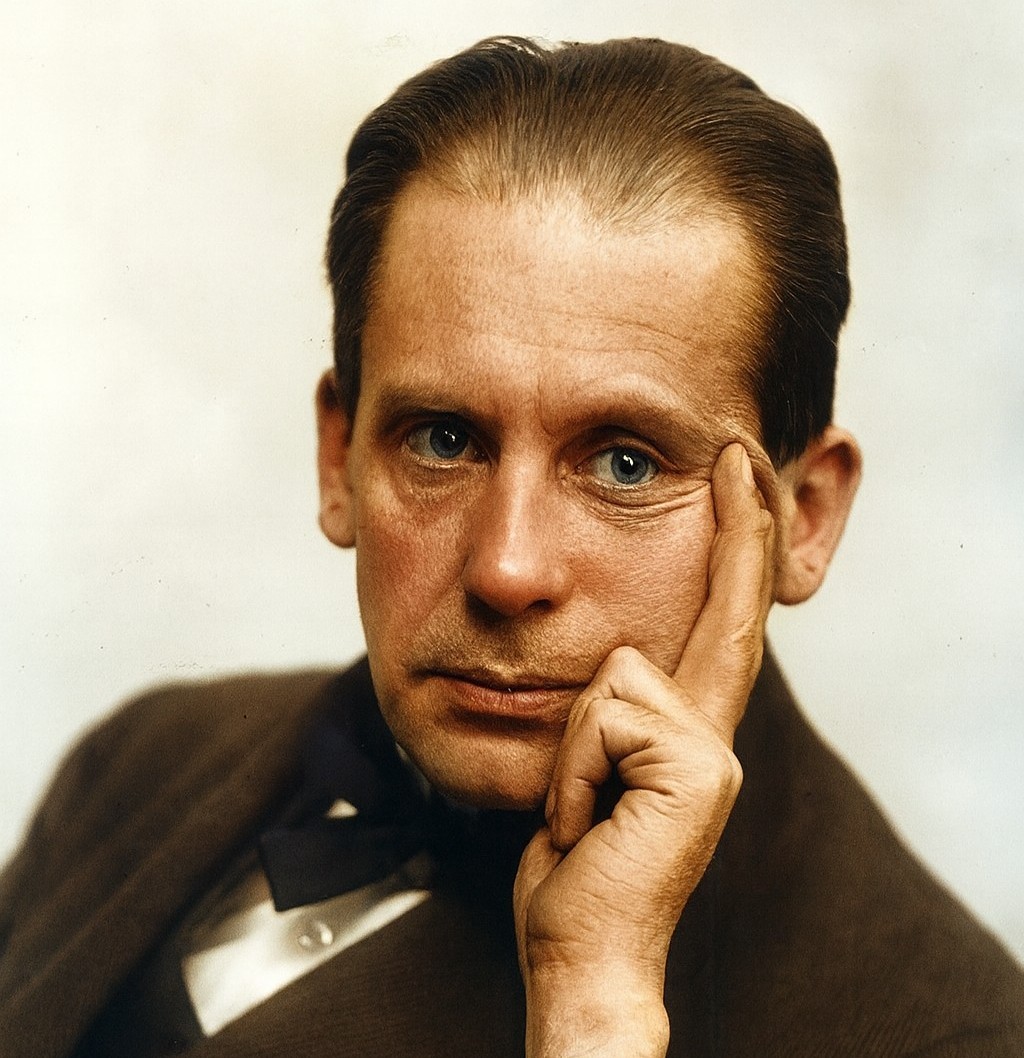

Walter Gropius stands among the most influential architects and educators of the twentieth century, best known for founding and shaping the Bauhaus, a school and movement that redefined the relationship between art, craft, industry, and everyday life. Born into a milieu that combined technical training and cultural engagement, Gropius brought to the Bauhaus a conviction that design should be socially purposeful and technologically literate. His leadership transformed a postwar cultural moment—marked by social upheaval, industrial expansion, and a search for new forms—into a coherent program for design education and practice that would ripple across continents for decades.

Gropius’s early career prepared him for the synthesis he later pursued at the Bauhaus. Trained in German technical schools and apprenticed in the office of Peter Behrens, he absorbed an approach that treated architecture as an integrated discipline, one that could coordinate structure, ornament, and industrial production. The experience of World War I and the social dislocations that followed deepened his belief that architecture and design must address collective needs rather than merely serve elite tastes. He saw in mass production the potential to improve living conditions and believed that architects and artists should collaborate to create objects and buildings suited to a democratic, industrial society.

In 1919 Gropius founded the Staatliches Bauhaus in Weimar, uniting an academy of fine arts and a school of applied arts under a single institutional roof. He articulated a manifesto that called for the abolition of the traditional separation between artist and craftsman and proposed a workshop-based curriculum that would unite fine art, craft, and industrial production. The Bauhaus was conceived not simply as a school but as a laboratory for reimagining everyday life through design. Gropius recruited an extraordinary faculty—painters, sculptors, and craftsmen such as Lyonel Feininger, Paul Klee, Wassily Kandinsky, and later László Moholy-Nagy and Josef Albers—creating a cross-disciplinary environment where painting, weaving, metalwork, and architecture informed one another.

Central to Gropius’s vision was a pedagogy that privileged making and material understanding. He reorganized instruction around a preliminary course designed to break students of academic habits and open them to experimentation in form, color, and material properties. This foundation led into specialized workshops—carpentry, metal, textiles, ceramics, and typography—where students learned techniques and production logic before moving toward more conceptual work. The workshops were not isolated crafts but nodes in a network that fed architectural thinking and industrial design practices. Gropius insisted that the school maintain close ties to industry, encouraging projects that could be realized through mechanized production and seeking partnerships with manufacturers. For him, reproducibility and standardization were not aesthetic dogmas but moral imperatives: good design should be accessible to many, not a luxury for a few.

Architecture occupied a central place in Gropius’s program. He believed the architect should be the synthesizer of the arts, coordinating structure, surface, and interior to produce coherent environments. Under his direction the Bauhaus developed a modern architectural language characterized by geometric clarity, flat roofs, ribbon windows, and an emphasis on volume over ornament. The Bauhaus building in Dessau, completed in 1926 and designed by Gropius, became an emblem of this aesthetic: its glass curtain walls, asymmetrical composition, and integrated workshop and studio spaces embodied the school’s ideals of transparency, functionality, and the fusion of art and technology. The building itself served as a pedagogical tool, demonstrating how form and program could be integrated to support new modes of work and living.

Gropius also championed experimentation with prefabrication and new construction methods, advocating for standardized components that could be assembled efficiently. He and his colleagues explored how mass production might be harnessed to create humane housing and efficient industrial facilities, and these experiments influenced social housing programs and postwar reconstruction efforts across Europe. The Bauhaus’s furniture and product designs—simple, functional, and suited to mechanized manufacture—illustrated how aesthetic restraint and technical rationality could produce objects that were both beautiful and practical.

Leading the Bauhaus required balancing visionary rhetoric with administrative pragmatism. Gropius was adept at attracting talent and funding and at framing the school as a cultural mission with social purpose. Yet the school’s radical program and left-leaning associations made it a target in the volatile politics of Weimar Germany. Pressures from conservative local authorities and rising nationalist forces forced the Bauhaus to relocate from Weimar to Dessau in 1925, and later to Berlin in 1932. Gropius resigned as director in 1928, handing the role to Hannes Meyer, but his imprint on the school’s structure and ethos remained decisive. The political climate ultimately proved fatal to the Bauhaus in Germany: the rise of the Nazi regime, which denounced modernist art as “degenerate,” led to the school’s closure in 1933. Many teachers and students emigrated, carrying the school’s ideas abroad and seeding modernism internationally.

Gropius’s own emigration and subsequent career helped internationalize Bauhaus principles. After leaving Germany he spent time in England and then emigrated to the United States, where he taught at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design and cofounded The Architects’ Collaborative. Through teaching, writing, and practice he transmitted Bauhaus principles—functionalism, integration of disciplines, and attention to industrial processes—to a new generation of architects and designers. The Bauhaus diaspora, including figures such as Marcel Breuer and Mies van der Rohe, played a central role in shaping the International Style and the postwar architectural landscape in North America and beyond. Gropius’s later projects, including academic buildings and collaborative housing, continued to reflect his commitment to teamwork, clarity of program, and the use of modern materials.

The legacy of Gropius and the Bauhaus is both pervasive and contested. On one hand, the school’s core contributions—an integrated approach to design, a pedagogy that privileges making and systems thinking, and a belief in design’s social responsibility—remain influential in architecture and design education worldwide. The Bauhaus’s visual vocabulary—clean lines, functional forms, and an economy of ornament—became shorthand for modernity in the twentieth century and continues to inform contemporary architecture, product design, and graphic communication. On the other hand, critics have argued that the Bauhaus’s embrace of standardization and industrial processes risked erasing craft traditions and individual expression. Gropius himself navigated these tensions, insisting that collaboration with industry need not mean the loss of aesthetic or ethical judgment.

Beyond stylistic influence, Gropius’s most enduring contribution may be institutional: he established a template for interdisciplinary collaboration that remains a touchstone for designers seeking to bridge art, craft, and industry. His emphasis on the social purpose of design anticipated contemporary concerns about sustainability, equity, and the public good. The Bauhaus model—preparatory training, workshop-based learning, and close ties to production—continues to shape how design schools organize curricula and how practitioners conceive of their role in society.

Walter Gropius’s role in the Bauhaus movement was foundational and far-reaching. He conceived and led an institution that reimagined the relationship between art and production, restructured design education around hands-on workshops and industrial collaboration, and articulated an architectural language suited to the machine age. Though the Bauhaus’s life in Germany was short, its ideas spread worldwide through exile, teaching, and practice, and Gropius’s influence endures in the way designers and architects approach problems of form, function, and social responsibility. His work remains a reminder that design is not merely about objects or buildings but about the conditions under which people live, work, and imagine better futures.